Background

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic, neglectful or violent experiences in childhood. Examples of ACEs range from child maltreatment and witnessing violence in the home to growing up with a parent with a mental health problem (1). Studies estimate that approximately 1 in 2 adults in England reports experiencing at least one ACE in childhood (2). ACEs are linked to considerable health burden in adulthood, and can substantially pressure families, health and social care systems (3).

The concept of adversity is not new. However, the term “ACEs” was first introduced by a groundbreaking study published in 1998 by the Centers for Disease Control and the Kaiser Permanente health care organization in USA, California. The concept of ACEs helped bring together and measure a diverse set of preventable adverse childhood experiences that can lead to considerable long-term health problems. The initial ACEs predominately referred to seven domains of adversity in the home environment, including child maltreatment (1. psychological abuse, 2. physical abuse, 3. sexual abuse) and household dysfunction (4. substance abuse in the household, 5. mental illness in the household, 6. mother treated violently, 7. criminal behaviour in the household). Sometimes the original domains are referred to as the “ten ACEs” when including “physical neglect”, “emotional neglect”, and “parental separation”.

Challenges in defining ACEs

Since the late 1990s, the initial “ACE domains” have undergone numerous expansions across studies. Whilst this variation helped innovate and adapt indicators of ACEs to different goals, there is currently little consistency in the definition and inclusion of ACEs. The large variation of measured ACEs also means there is no agreed reference standard for developing new measures of ACEs. Previous studies have mainly assessed the validity and relevance of ACEs based on their risk association with poorer health outcomes in adulthood. However, most studies reporting on the negative health effects of ACEs are based on cross-sectional samples of adults asked to recall experiences from childhood (1). Recent birth cohort studies, however, reveal that ACEs are relatively poor predictors of negative health outcomes in adulthood relative to other socioeconomic factors (2). Global studies by the World Health Organization show that traumatic stress symptoms naturally resolve on average six years after a linked traumatic event (e.g., an ACE),(3),(4). These gaps create multiple challenges when attempting to develop new indicators of ACEs for electronic health records (EHRs).

Establishing a consistent definition and an integrated conceptual model of ACEs

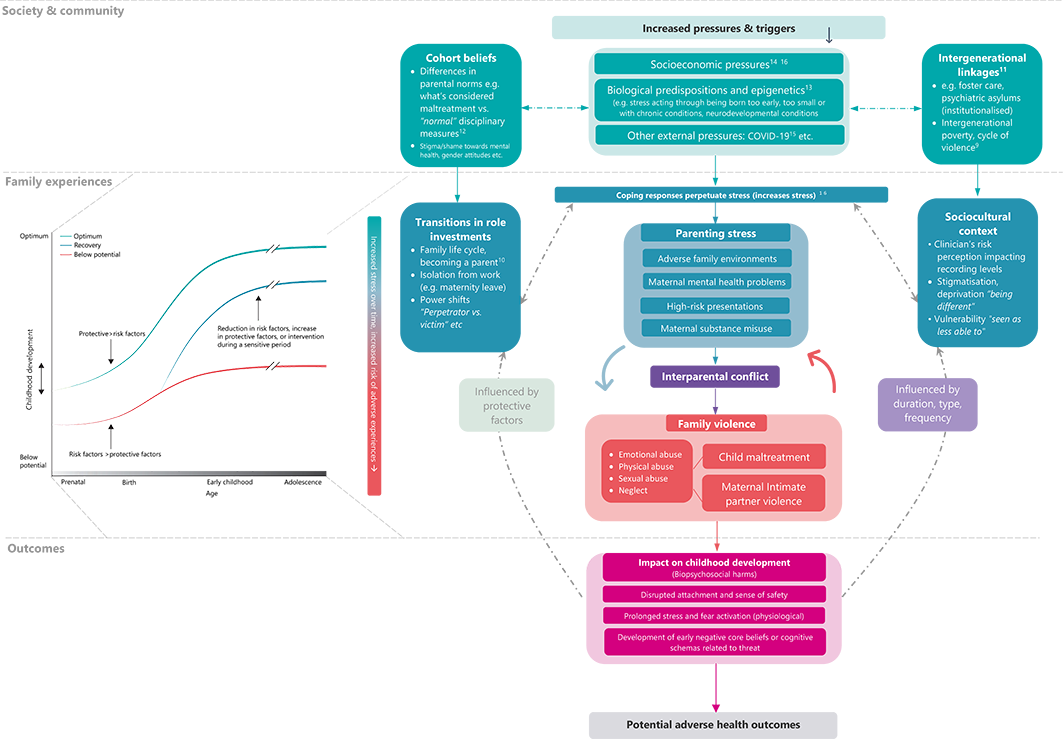

To promote a clearer understanding of developing ACE indicators, we developed a set of criteria to define ACE indicators. We developed a “testable” conceptual biopsychosocial model to help generate theoretically informed predictions of which ACE indicators might be more relevant than others. We have summarised this integrative conceptual model and the pre-specified definition of ACEs below.

Definitions and inclusions

We defined ACE indicators as any experience within the family environment recorded in the child or the maternal record considered to be:

- Frightening, violent, traumatic or neglectful (see WHO violence definition), with potential for immediate or longer-term harm to a child’s biopsychosocial development (intentionally or unintentionally) (see UK government definition), as caused by;

- A single significant event or through repeated exposure;

- Caused by external factors and not the child themselves, such as self-harm, and;

We made several adaptations to previously studied ACEs for feasible ascertainment in electronic health records (EHRs). We defined indicators as variables of grouped codes and measures. We aimed to develop ACE indicators that reflected clinically meaningful risk groups of adversity to identify families that may be eligible for targeted maternal-child care interventions in England (e.g. Supporting Families programme, or previously “targeted care pathway” of the Healthy Child Programme by Public Health England. See also WHO for intervention studies.

We manually grouped indicators into broader ACE domains consistent with the original study by Kaiser Permanente and CDC. Due to the lack of recordings, we collapsed all types of child abuse and neglect into child maltreatment (CM). We collapsed “imprisonment of household members” and “household challenges” into Adverse family environments. We created a separate indicator, “Social service involvement” (SSI), for social care-related codes that did not contain descriptions of CM or mIPV. Due to few recordings and high intercorrelations, SSI was merged with CM in the final selection process.

Given the substantial under-recording of CM and mIPV (e.g. see 1, 2), we also added the domain “high-risk presentations of CM” (HRP-CM). HRP-CM encompassed indicators from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Royal College of General Practitioners (RGCP) that should raise clinical suspicion for CM.

ACEs can be recorded in both parents’ and children’s records. ACEs are considered based on each specific child’s time from birth. Children are, therefore, considered unexposed if no relevant recording occurs during the study period, regardless of previous exposure to children within the same family. This approach mirrors changes in stress levels as the family moves through different life stages.

A biopsychosocial conceptual model for defining and developing ACEs

We developed a “testable” conceptual, integrative biopsychosocial model to help better understand ACEs and generate theoretically informed predictions of which ACE indicators might be more relevant than others. In this model, we integrate theories from the socio-ecological system theory by Bronfenbrenner (1977) and Belsky (1980) as a platform to map other theories relevant to ACEs within two ecological levels (the individual and the family environment). By focusing on the first two ecological levels, we restricted ACEs to clinically measurable and intervenable indicators at a family level.

Across these two “ecological” levels, we make predictions of relevant ACEs based on attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969–82; Ainsworth et al., 1978), the cumulative stress model (includes the “allostatic load” model and the “ecobiodevelopmental” framework), and cognitive behavioural theories of emotions.

Below, we summarise different key theories and mechanisms hypothesised to play a role in ACEs. It does not represent an exhaustive list.

Download the figure in high resolution.

The figure does not represent an exhaustive list of potential mechanisms behind ACEs.

Society & community level

Social determinants of health encompass socioeconomic conditions that shape health outcomes for individuals, families and communities. Children with ACEs are more likely to grow up in environments where raising a family and coping with everyday challenges is harder. Families may live in communities with high unemployment and a lack of local resources for families, with parents having to travel long distances to work, or family members may be more likely to suffer from health problems that make it difficult to work.

Individual & family level

Attachment and learning theory. Social risk factors can negatively influence carers’ ability to respond, such as being available and responsive to a child’s attachment cues. Children with ACEs may be more likely to develop insecure attachments from reduced caregiving responses of emotional validation (e.g., “my pain matters”) and reduced experiences of healthy parental modelling of emotion regulation. This can also mean a child loses friends and the support of adults and misses out on opportunities to grow social support networks.

Cognitive and behavioural theories. People cope with stress and perceived threats using different preventative strategies (e.g. avoidance, escape, fight) to minimise negative consequences. Children who grew up in environments with increased levels of stress and unpredictability can be more likely to perceive the world as less safe and feel less confident they can manage. To cope, children may develop cognitive biases toward threats, learn to suppress emotions, and avoid situations they fear will cause further distress (e.g. see theories on emotional processing, selective attention and overestimation of threat). Over time, however, this interaction of biopsychosocial factors prevents new learning of balanced threat appraisals (e.g. “I can cope”), creating a maintenance cycle of stress.

For some families, these social risk factors and coping responses are carried over across generations as children become parents themselves. Whilst strategies are perceived as logical at the moment, over time, they can leave families in a cycle that perpetuates stress (e.g. avoidance prevents learning from experience). As underlying stress increases, caregivers and children have fewer resources to cope and regulate responses (e.g. reduced response inhibition/executive functioning)(6), increasing the risk of more immediate coping responses to escape or re-gaining control (e.g. shouting, violence, neglect etc.).

Coping responses may vary as a function of the level of need to escape distress and harm, ranging from immediate escape (e.g. violence, substance misuse, abandonment/neglect) to stronger forms of avoidance (e.g. avoiding going out, which reduces social support systems in the longer-term) (7)

Life-course approach. Taken together, the model views ACEs as a complex social phenomenon and considers families as resilient and constantly striving to cope using different strategies and resources at hand (e.g. protective factors). The model also helps separate the adverse experience from the adverse stress response of the child, overcoming previous study limitations of [reverse causality] when looking at long-term outcomes. We consider ACEs recorded at the family level (middle segment) amenable to service level intervention and relevant to electronic health records (see above for all criteria).

A multistage risk prediction model to determine relevance of candidate ACEs (increased adversity –> increased risk of family violence)

We assessed the relevance of identified candidate ACE indicators based on their consistent risk association with a reference standard of family violence in a multistage prediction model. The reference standard (outcome) was any occurrence of child maltreatment (CM) and maternal intimate partner violence (mIPV) up to 5-years post-birth.

Consistent with our theoretical model, we predicted that the final ACE indicators would reflect a continuum of clinical relevance, ranging from a high risk of family violence (i.e. high need for intervention) to lower relevance, consistent with previously studied ACEs domains.

|

|